Underwriting a real estate deal is rarely about finding the “right” metric. More often, it is about understanding how multiple signals interact and whether they tell a coherent story. Problems usually arise not because a metric is wrong, but because it is interpreted in isolation, out of sequence, or without sufficient scrutiny of the assumptions, definitions, and omissions behind it.

Underwriting metrics such as Cap Rate, NOI, Pro Forma projections, Unlevered Free Cash Flow, Yield-on-Cost, IRR, Cash-on-Cash Return, Equity Multiple, Debt Yield, DSCR, and Loan-to-Value (LTV) are designed to answer different questions. When they are treated as standalone verdicts, they tend to obscure risk rather than clarify it. Financial analysis becomes more reliable when these underwriting metrics are read together, with explicit attention to how they relate, what they exclude, where they are most sensitive, and which components of return are driven by operations versus residual value.

This page is designed as a decision-support hub for real estate underwriting. It does not redefine individual metrics, but explains how underwriting metrics fit together in practice, how they should be sequenced, and where institutional standards require stricter interpretation.

Key Underwriting Metrics Covered in This Guide

This guide focuses on how underwriting metrics work together in real estate analysis, not how they are calculated in isolation. Key underwriting metrics discussed include:

- Net Operating Income (NOI) — operating performance before financing and capital costs

- Cap Rate (Going-In vs. Exit) — market pricing of income, not a return metric

- Unlevered Free Cash Flow (UFCF) — cash generated after capital expenditures and leasing costs, before financing

- Yield-on-Cost (YoC) — stabilized NOI relative to total invested capital

- IRR (Income Return vs. Appreciation Return) — timing and composition of equity returns

- Equity Multiple — total magnitude of equity return

- Cash-on-Cash Return — current income yield on invested equity

- Debt Yield — leverage and refinance risk indicator

- DSCR (Debt Service Coverage Ratio) — cash flow coverage of debt obligations

- Interest Coverage Ratio (ICR) — sensitivity to interest rates and amortization

Each underwriting metric is examined in context, with emphasis on sequencing, interaction, and downside protection.

The Relationship Between Cap Rate, NOI, and Cash Flow in Underwriting

Financial analysis works best when underwriting metrics are treated as signals within a system rather than conclusions on their own. Each metric highlights a different layer of the deal, and none is sufficient by itself to support an investment decision.

- Cap Rate reflects how the market prices income.

- NOI describes operating performance before financing and taxes.

- The Pro Forma formalizes assumptions about future behavior.

- Unlevered Free Cash Flow tests whether those assumptions translate into distributable cash after capital expenditures, tenant improvements, leasing commissions, and replacement reserves, but before financing.

At this stage, it becomes critical to distinguish between physical occupancy, economic occupancy, and economic vacancy, as realized cash flow depends on more than whether units are occupied.

The gap between physical and economic occupancy is driven primarily by loss to lease, concessions, and bad debt. A property can appear operationally healthy based on physical occupancy while materially underperforming at the cash-flow level due to rent under-collection, delinquency, or below-market leases. Underwriting that fails to isolate these drivers systematically overstates cash durability.

Return metrics such as IRR, Equity Multiple, and Cash-on-Cash Return then translate not only the timing but also the composition of cash flows into an investor decision framework. At this stage, it becomes critical to distinguish between income-driven returns and appreciation-driven returns, as they represent fundamentally different risk profiles.

When underwriting metrics align, the deal tends to be resilient. When they diverge, that divergence usually signals optimistic assumptions, structural fragility, or hidden risk.

The Real Estate Underwriting Process

The underwriting process begins with assumptions formalized in the Pro Forma, including expected rents, vacancy, concessions, expense growth, capital expenditures, tenant improvements, leasing commissions, replacement reserves, financing terms, and exit conditions. These assumptions are hypotheses only, and must be anchored to trailing financials, rent rolls, observed market data, and market absorption to avoid double-counting, overstated cash flow, or inflated returns.

From these assumptions, operating performance is derived and expressed through NOI, which reflects income before financing and taxes but excludes CapEx, TI/LCs, and replacement reserves. Because these are real economic costs, they must be deducted to arrive at Unlevered Free Cash Flow (UFCF), treating reserves as “soft” line items systematically overstates cash generation.

Valuation cross-checks accompany cash flow analysis. In-place NOI implies a going-in cap rate, while stabilized NOI combined with an exit cap rate determines reversion value. That said, although automated valuation models (AVM) are sometimes used as initial pricing references, they cannot capture capital intensity, lease structure, or cash-flow durability and should not substitute for underwriting based on NOI and UFCF.

To meet conservative underwriting standards, exit cap rates is applied—typically 50–100 basis points—to reflect asset aging, housing market conditions, and capital market risk. For value-add and development strategies, Yield-on-Cost (YoC) measures stabilized NOI relative to total invested capital, and a YoC spread of 100–150 basis points over the market cap rate is generally required to justify execution risk.

Finally, equity-level underwriting metrics—IRR, Equity Multiple, and Cash-on-Cash Return—translate levered cash flows into decision metrics. Compressing assumptions directly into IRR without this sequencing tends to hide fragility.

How Operating Metrics and Valuation Metrics Interact in Real Estate Underwriting

Operating metrics describe what the asset generates. Valuation metrics describe how the market prices that generation.

NOI directly influences value, but Cap Rate does not purely reflect operating quality. Two assets with identical NOI can trade at very different cap rates due to location, growth expectations, liquidity, regulatory environment, and capital market conditions. Cap Rate should therefore be interpreted as a pricing signal, not a return metric.

Distinguishing between going-in and exit cap rates is critical. Exit cap assumptions often do more work in driving returns than operating improvements and must be explicitly stress-tested.

Screening tools such as Gross Rent Multiplier, the 1% Rule, and the 7% Rule function as triage mechanisms only. They cannot account for capital intensity, lease structure, financing terms, or volatility and should never substitute for underwriting.

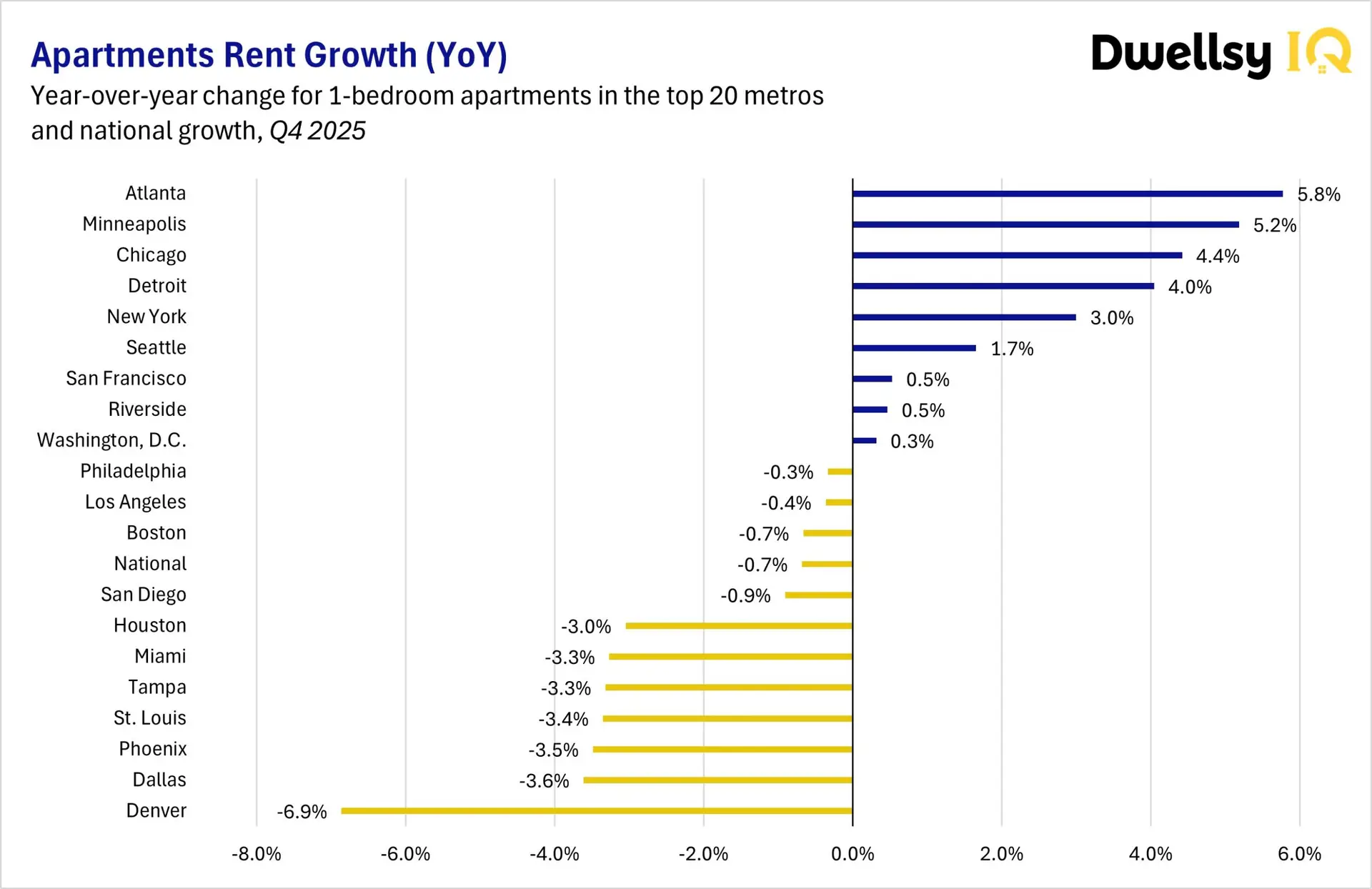

In the current U.S. interest rate environment (2024–2026), rules like the 1% Rule are largely decoupled from market reality, particularly in core and high-growth MSAs. In many institutional and coastal markets, assets that meet a strict 1% threshold are either distressed, structurally impaired, or mischaracterized. Treating the absence of a 1% Rule signal as a negative indicator in today’s environment often results in false negatives rather than prudent risk avoidance.

Used correctly, screening rules save time. Used incorrectly, they create false confidence or eliminate viable deals before underwriting begins.

How to Stress-Test Debt in Real Estate Underwriting (DSCR, Debt Yield, ICR)

Debt introduces a second analytical lens: survival under stress.

DSCR measures cash flow coverage of total debt service and includes principal amortization. Interest Coverage Ratio (ICR) isolates interest burden. In interest-only structures common in bridge and value-add financing, DSCR and ICR are effectively identical. Risk emerges when the interest-only period ends and amortization begins.

A deal that appears healthy at a 1.50× DSCR during the IO period may deteriorate rapidly once principal payments start. Amortization sensitivity must be explicitly tested.

Debt Yield measures NOI relative to loan amount and serves as a leverage floor independent of interest rates or amortization. While traditional underwriting often cited an 8% Debt Yield as a baseline threshold for CMBS and agency executions, in higher-rate environments lenders have increasingly pushed required floors upward.

In practice, Debt Yield thresholds today typically range from 8% to 10%, with higher requirements applied to assets with elevated volatility, weaker liquidity, or structural risk—most notably in certain Office and transitional property types. A deal that fails to clear these thresholds may appear viable on DSCR in the near term but remain structurally impaired at refinance or exit.

Effective stress-testing focuses on identifying failure points, not passing minimum hurdles.

How Capital Structure Changes the Meaning of Underwriting Metrics

Capital structure materially alters how underwriting metrics should be interpreted. Metrics observed before leverage describe asset durability; equity-level metrics describe return volatility.

Unlevered Free Cash Flow anchors the analysis in economic reality. Levered IRR and Equity Multiple amplify leverage, timing, and exit assumptions. Attractive equity returns can coexist with fragile assets, while conservative leverage may suppress returns but materially reduce downside risk.

Understanding the full capital stack—including LTV, amortization, covenants, reserves, and subordinate capital—is essential for accurate interpretation.

How Lease Structure and Expense Assumptions Distort Underwriting Metrics

Two deals with identical NOI can behave very differently once lease structure and expense assumptions are examined.

In commercial assets, lease structure shifts operating risk between landlord and tenant. In multifamily assets, utilities, concessions, turnover, delinquency, and make-ready costs dominate cash flow volatility.

Replacement reserves must be treated as real economic costs. Sellers often understate them to inflate apparent cap rates. Buyers who treat reserves lightly systematically overpay.

When Underwriting Metrics Conflict: What to Trust and Why

Conflicting signals are diagnostic. A strong cap rate paired with weak DSCR indicates leverage risk. Healthy NOI with weak UFCF signals capital intensity. A compelling IRR driven primarily by exit assumptions signals residual value dependency.

In institutional underwriting, IRR is often partitioned into Income Return and Appreciation Return. If more than 70% of IRR is driven by sale proceeds, the investment is primarily a bet on appreciation rather than operating performance.

Metrics closest to cash durability, downside protection, and refinance survivability should dominate interpretation.

Where Screening Rules Fit in a Real Estate Underwriting Workflow

Screening rules function best as triage tools. Their usefulness collapses beyond initial filtering, particularly in low-cap or capital-intensive environments.

Used correctly, they save time. Used incorrectly, they create false confidence.

How Underwriting Metrics Should Be Weighted by Strategy and Asset Type

Core strategies prioritize NOI durability, UFCF stability, and debt resilience. Value-add strategies depend heavily on YoC spreads, execution risk, and transitional cash flow. Opportunistic strategies tolerate volatility but require precise identification of risk concentration.

Time horizon and exit dependency fundamentally change how underwriting metrics should be weighted.

The Most Common Real Estate Underwriting Mistakes

Common underwriting failures include ignoring cap rate expansion, overstating cash flow by softening reserves, relying on exit-driven IRRs, and failing to separate income return from appreciation return.

These issues rarely appear obvious in base-case models but surface quickly when assumptions break.

FAQ about Real Estate Underwriting Metrics

What are underwriting metrics in real estate?

Underwriting metrics are financial indicators used to evaluate risk, cash flow durability, and return composition in a real estate investment. Examples include NOI, cap rate, unlevered free cash flow, yield-on-cost, IRR, debt yield, and DSCR.

Is cap rate a return metric?

No. Cap rate is a pricing metric that reflects how the market values income. It does not account for capital expenditures, financing, or cash flow timing.

What does unlevered free cash flow include?

UFCF starts with NOI and subtracts capital expenditures, tenant improvements, leasing commissions, and replacement reserves. It represents asset-level cash generation before financing.

What is a good yield-on-cost for value-add deals?

Yield-on-cost should generally exceed the stabilized market cap rate by at least 100–150 basis points to compensate for execution and leasing risk.

Why can IRRs be misleading in underwriting?

IRRs can look attractive when returns are dominated by exit value rather than operating cash flow. High residual value dependency increases exposure to capital market risk.